Financial markets move for various reasons. Economic data is the factor that most influences the daily market price action. Geopolitical events are responsible for medium- and long-term gyrations in markets. In response to all new information and data that hits the market, the successful fundamental trader must interpret the respective monetary and fiscal policies. Fundamental analysis means taking a position in the market based on interpreting economic data and various events at the micro and macro levels.

For example, a country's economic performance determines its currency's strength. The FX dashboard comprises currency pairs, and an exchange rate shows the value of 1 currency compared to another. Economic differences between countries are responsible for a big part of the market’s volatility.

Monetary policy is the decisive element for the markets. This is why the meetings at central banks and interest rate decisions move financial assets aggressively. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, refers to the actions taken by governments regarding borrowing or taxing the population. Simply put, central banks set monetary policy, while governments set fiscal policy.

This article aims to present the differences between the 2 and explores their impact on various markets. The timing could not be better, as the COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented measures taken by central banks and governments around the world, both in the monetary and fiscal spaces.

Financial markets spend most of the time in consolidation. But when they move, they move for a reason, and that reason typically involves changes in the monetary or fiscal space.

Many traders, especially those that use technical analysis, view monetary policy as boring. Also, few understand the implications of changes in the fiscal space. This is why this article is mandatory for anyone with an interest in financial markets.

Monetary Policy

If there is 1 thing that moves global markets, it’s monetary policy. Monetary policy refers to a central bank’s decisions on interest rates – this is the basic definition.

But these days, monetary policy has evolved. After the 2008–2009 Great Financial Crisis, monetary policy went beyond simply moving the interest rates.

Up to that point, central banks in the developed world had reacted to economic performance by raising or cutting rates. A stronger economy usually has rising inflation, so the central bank hikes the rates to cool inflation. The opposite happens when the economy is weak.

In the aftermath of the 2008–2009 Great Financial Crisis, central banks were left with rates close to the lower boundary, but advanced economies still needed support. As such, unconventional policies were introduced, such as Quantitative Easing (QE) programs. Under such programs, the central bank buys its own government bonds and thus floods the market with fresh liquidity.

Monetary policy is, thus, set by central banks and central banks only. They meet regularly, typically every 6 months in the developed world, and assess the state of the economy.

Most central banks have a mandate from the government. Price stability is the cornerstone for any central bank, and price stability is defined by a certain level of inflation.

But not all central banks have a similar mandate. The mandate differs and may change over time. After the Bretton Woods agreement was dumped by the United States in the 1970s, fiat currencies started to float freely. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was the 1st one to tie its monetary policy decisions to price stability, and other central banks quickly followed suit with similar mandates. It is normal for central banks to have an inflation-targeting framework, although the definition of inflation, as well as the target, may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

What Drives Changes in Monetary Policy?

Monetary policy changes for 2 main reasons – economic developments and changes in inflation. Central banks closely monitor the economic developments in the economy. They analyze the data released in between meetings and then react accordingly.

If the economic data is better than expected, the central bank will, over time, signal an upcoming change in the monetary policy. Tightening financial conditions is warranted during periods of economic strength. Tightening may take various forms, and the most obvious is to raise the interest rate. The official interest rate has various names in different parts of the world – “cash rate” in Australia, “key interest rate” in the Eurozone, and “federal reserve funds rate” in the United States.

But central banks have other tools to tighten financial conditions, depending on the monetary policy stance. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, all central banks in advanced economies engaged in QE programs. They bought a certain amount of bonds every month. Tapering the bond purchases is a form of tightening financial conditions.

Inflation is a key concern for central banks. The definition of price stability differs from country to country, but all central banks in developed economies want to create inflation around the 2% level, which is considered the optimal level for sustained economic growth.

But central banks had a hard time creating inflation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, some, like the European Central Bank (ECB), had their interest rate below zero before the pandemic started.

The ECB sets 3 interest rates, not just 1. Their average is close to zero, but the deposit facility rate, the most important one, was in the negative territory before the pandemic. Low inflation and even deflation were responsible for setting the monetary policy in negative territory.

Most Relevant Central Banks’ Decisions

Not all central bank decisions have a similar impact on the currency market. Some may move the markets more than others.

Certainly, any central bank may surprise market participants and trigger some sharp movements on the currency market. But no central bank wants to do that, for the simple reason that unnecessary volatility is not in anyone’s interest.

Federal Reserve of the United States

The financial markets stand still when the Federal Reserve of the United States (Fed) is deciding the monetary policy for the period ahead. Every 6 weeks, on a Wednesday, the Fed releases its decisions.

First, a FOMC Statement comes out, in the 2nd half of the North American trading session. Half an hour later, a press conference follows.

Not all meetings are equally important – those that present the staff projections during the press conference are the most relevant ones. The U.S. dollar is extremely volatile during such times, as the Fed’s decision influences all markets – bonds, stocks, and commodities.

European Central Bank

The ECB also meets every 6 weeks, this time on a Thursday. Just like the Fed, the ECB first issues its decision, and then, 45 minutes later, a press conference follows.

During the press conference, the President of the ECB first reads the statement and then takes questions from financial media representatives. The common currency, the euro, moves aggressively following the ECB’s communication, regardless of whether the market was prepared for the forward guidance or not.

Other Central Banks to Consider

The rest of the central banks in the G10 world meet either every 6 weeks or monthly. The Reserve Bank of Australia, for example, meets monthly, on the 1st Tuesday of the month.

But its decisions rarely move markets. As such, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan’s meetings and monetary policy announcements move the markets only in the event of a surprise. Out of all these central banks, the Bank of Canada is the one that delivers most of the surprises, because it guides part of its monetary policy decisions on changes in the price of crude oil.

Unconventional Policies

Unconventional policies refer to other central bank decisions besides changes in the interest rate. Sure enough, central banks set various interest rates. For example, the Fed in the United States also sets the interest on excess reserves. Changes in this interest rate are still viewed as conventional policies.

When inflation declines, central banks lower their interest rates. This way, commercial banks are more interested in providing loans to businesses and the population rather than parking their reserves at the central banks. Also, the population and businesses are interested in borrowing because interest rates are lower. Thus, the economy grows again.

But what do you do as a central bank when the interest rates are already close to the lower boundary and there is no economic recovery, or when inflation remains stubbornly low?

The perfect example comes from Japan. For decades, the Bank of Japan has struggled to bring inflation close to its target, despite having some of the loosest financial conditions in the world.

Unconventional policies appeared from the need to do more. Central banks quickly became innovative in the monetary policy space.

Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing, or QE, refers to the process of a central bank buying bonds issued by the government. For example, under the QE program in the United States to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed buys $120 billion worth of bonds every month – $80 billion worth of U.S. Treasuries and $40 billion in mortgage-based securities.

The result of the QE program is that the money supply available in the economy rises. As a result, inflation should rise as well, but that happens only if the velocity of money increases as well.

Any deviation from the initial QE plan is viewed as tightening or easing. For instance, after the 2008–2009 Great Financial Crisis, the Fed ran multiple QE programs. Every new plan brought more liquidity to the markets, and the financial conditions eased beyond a simple reduction in the interest rate. As such, the U.S. dollar declined, and other fiat currencies gained against the greenback.

Tapering the QE program means that the central bank buys fewer bonds. The easing is ongoing, but at a slower pace. Therefore, when compared to the earlier standing, financial conditions have tightened.

QE was quickly adopted by other central banks, and now everyone uses the tool as an unconventional measure in times of need. In some parts of the world, like the European Union, the bond-buying process is a bit more difficult because of the different governments in Europe and different debt issuers. Yet, the ECB has found the way to properly use QE programs.

The Rise of the Importance of Climate Change

One area growing in importance is climate change. Most recently, the ECB included climate change on its agenda, meaning that it will have special financing conditions to stimulate the fight against climate change.

Recent years have brought natural disasters all over the world. From hurricanes, to wildfires, to extreme heat or cold, all are the result of climate change.

Because of that, central banks have stepped up their regulations against climate change. They now favor projects that reduce their carbon footprint. Expect this trend to continue in the future and to be quickly adopted by other central banks around the world.

To offer an example, imagine that the central bank decides to help companies investing in green projects when deciding which bonds to buy under the QE program. Alternatively, they may simply deem bonds that end up harming the environment as not eligible for the QE program.

Why Do We Need Inflation?

People often wonder why we even need inflation. It is difficult to build a case for inflation because inflation means rising prices for goods and services. Because wages do not rise as fast, inflation literally “eats” from people’s income.

In other words, the money earned will buy you less if inflation is bigger than wage growth. No one wants that!

If inflation rises more than the central bank’s target, the bank intervenes by raising the interest rates. The key here is not to do it too early or too late.

In the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to inflation overshooting the Fed’s target. As the chart above shows, the CPI jumped while the rates remained at zero. So why did the central bank not raise the rates?

The answer comes from future inflation expectations. If the central bank is convinced that higher inflation is transitory, like the Fed is, then it will prefer to remain behind the curve and wait a bit more to see if that is the case indeed. The risk, however, is that inflation may get out of hand, just like it did in the past.

Inflation stimulates economic growth. If the population and businesses have the impression that prices will increase in the future, they will not postpone consumption and will act now. By consuming now and not postponing the process, the economic growth picks up, and economic expansion follows.

Are All Markets Affected by Changes in the Monetary Policy?

Yes. Financial markets are correlated. A sharp correction in the stock market could lead to a stronger Japanese yen and Swiss franc. When this happens, the euro and the Australian dollar also decline, for example.

When a central bank raises its rates, that is bullish for the currency. If that bank is the largest in the world, as the Fed is, higher interest rates on the dollar will have repercussions for the global economy.

Plus, central banks in the developed world rarely have diverging policies. In other words, when the Fed raises or lowers its rates, other central banks follow suit. Also, when the Fed moves the rates on the world’s reserve currency, it affects the volatility in emerging markets, too. Because most of the debt in emerging markets is issued in U.S. dollars, this means that higher U.S. rates will make it more expensive for emerging economies to repay their debt.

Monetary Policy during Economic Recessions

The 1st move during a recession is to lower the interest rates. Depending on the severity of the economic shock, the central bank may decide not to wait until its next meeting to act.

It has happened in the past that the Fed has cut the rates between 2 meetings for the simple reason that it would have taken too long to wait. Moreover, the central bank’s monetary policy decisions need time to propagate through the economy. In other words, the effects of today’s decisions will be visible in time, not right away. This is a major difference between fiscal and monetary policies.

Fiscal Policy

Monetary policy decisions are made by central banks. In sharp contrast, fiscal policy decisions are made by governments.

Through fiscal policy decisions, the government tries to influence the macroeconomy in areas such as aggregate demand, employment, and inflation. Fiscal policy must be coordinated with monetary policy. For example, fiscal policy decisions may lead to changes in inflation, and the central bank will be forced to react.

Perhaps there is no better time to talk about fiscal policy than after the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic led to a shutdown of the global economy as countries around the world entered lockdown.

To support their economies, governments came up with emergency solutions. Some borrowed extra money to fund unemployment schemes, some already had the money to expand the fiscal support, and so on. The measures in the fiscal space were so aggressive that we even saw “helicopter money” – a controversial concept by which people receive free money from the government in exchange for nothing.

Instead, the government simply hopes that the money will be spent and that the economic downturn will not last long.

But things are not that simple. During economic downturns, uncertainty is high. As such, households adopt a wait-and-see approach, hesitating to spend all the money they receive, and so the savings rate increases. In time, as the economy reopens, the savings rate declines to normal levels.

The main point to remember here is that fiscal policy refers to governments, while monetary policy refers to central banks.

The Cost of Borrowing

The easiest way to think about fiscal policy is to compare the finances of a country to the finances of a household. The comparison is not 100% accurate, but it offers a clear glimpse into what drives public debt.

Each country has a treasury department. The fiscal policy in any country is separate from its monetary policy. This is 1 of the main drags on the euro and the European Union: euro detractors argue that the European Union is incomplete unless it integrates its fiscal policies. Hence, the United States, which is a larger economy than the Eurozone economies, will always have an advantage unless the European Union integrates its fiscal policies.

Just like households, a country has revenues and expenses. For most families, a household’s revenues are salaries and wages, supplemented by rent, dividends, or other means designed to improve the household’s financial position. In contrast, a countries’ revenues are mainly taxes – think about VAT, fuel taxes, and so on.

Some countries are privileged. For example, oil-producing countries such as Qatar or Norway have significant revenues from the extraction and production of oil and invest or save that revenue for future consumption.

But not all countries enjoy such financial freedom. In fact, most live beyond their means – effectively, they spend more than they have. When expenses exceed revenues, the country has a budget deficit. To cover for the difference, countries, just like households, borrow money.

Bonds vs. Yields and Other Correlations

Governments can issue bonds to borrow from international markets. Bonds are attractive to investors because they guarantee future cash flows.

Depending on the country that issues the bonds, they can be more or less attractive to investors. For example, the U.S. ten-year Treasury bond is seen as the equivalent of a risk-free asset. Effectively, this means that investors do not believe that the U.S. can default on its debt. Other bonds have similar qualities, such as the German Bund.

Bonds have a price and a yield. The higher the yield, the more attractive the bond is. The price of a bond and its yield have an inverse correlation, which means that when the yield rises, the price of the bond falls.

And this brings us to the connection between monetary and fiscal policies. During the most recent economic recessions, central banks engaged in unconventional monetary policies such as buying bonds issued by their national governments.

When central banks buy bonds in large amounts, the price of the bonds tends to move to the upside because of the pressure on the buying side. Because of the inverse correlation mentioned earlier, the yields tend to decline.

In other words, the central banks’ actions make fixed income less attractive to investors. In many cases, the yields decline even below zero, so investors are forced to look for other alternatives, such as the stock market or alternative investments.

Easy or Tight Fiscal Policy

Just like monetary policy, fiscal policy can be easy or tight. When central banks ease their monetary policy, they do so by cutting interest rates. If the interest rates are already at the lower boundary, central banks engage in more easing via unconventional monetary policies.

In contrast, governments may ease the fiscal policy by cutting taxes, for instance. If the consumer spends less on taxes, the government’s revenues decline, but there is more left for the consumer to spend in the economy. Hence, easy fiscal policy stimulates economic growth just like easy monetary policy does.

But the 2 are not correlated. This means that easy monetary policy is not always accompanied by easy fiscal policy. As has often been the case in the past, the fiscal policy may be tight while the monetary policy is loose. All in all, central banks and governments try to find a balance between the 2 in such a way to optimize revenue growth while stimulating economic growth.

The U.S. Treasury

The U.S. Treasury is the national treasury of the U.S. government. The U.S. Treasury has a general account at the Federal Reserve of the United States, where it holds it revenues from issuing debt.

Among its other functions, the U.S. Treasury is responsible for collecting taxes and managing federal finances. The U.S. Treasury is 1 of the most respected institutions in the United States, and the head of the U.S. Treasury has a tremendous impact on financial markets.

Monetary and fiscal policies are often run by the same people. The best example comes from the former Chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen. After she served for many years as the Fed Chair, she was appointed to run the U.S. Treasury, which she accepted. This shows us that monetary and fiscal policies are interconnected and that central bankers have no problem running the national treasury of a country.

Fiscal Policies During COVID-19

We cannot end this article without mentioning the COVID-19 pandemic. The fiscal response to the pandemic was unprecedented, as governments had to innovate and take bold steps to tackle the economic downturn.

The monetary policy response was somewhat similar to the one following the Great Financial Crisis in 2008–2009. Central banks lowered the interest rates to zero immediately and then started buying bonds.

Even here, some things are worth mentioning – for the 1st time, central banks started to buy corporate bonds too, not only government bonds. Also, because all the central banks in developed economies had the same reaction, the stimulus had a global impact.

As impressive as the monetary response was, the fiscal response exceeded all expectations. Governments used all their reserves and leverage to make sure that people received unemployment benefits, that businesses had enough cash to survive, and so on.

Two things stood out from the crowd. One is the response of the European Union. For the 1st time in its existence, the European Union issued common debt.

Remember that earlier in the article, we mentioned that 1 of the flaws of the European Union is that it does not have a common fiscal policy. Well, COVID-19 changed that, and a precedent now exists. Europe issued common debt, the closest thing to European bonds, and the market’s appetite for the bonds exceeded all expectations – the issuance was oversubscribed multiple times.

The other thing that stood out is helicopter money. For the 1st time ever, money was sent directly to people’s accounts, with a simple recommendation – albeit not a requirement – to spend it. The United States led the way, sending weekly checks to households, and the results appeared immediately – economic growth followed, and U.S. households have saved over $1 trillion, an amount that, eventually, will find its way back into the economy.

European Union

Coming back to the European Union, the response was, once again, unprecedented. Dubbed the Next Generation EU, the plan expects most of the payments to be released in 2023 and 2024.

One of the key features of the Next Generation EU program is its Recovery and Resilience Facility. We’re talking about over EUR 700 billion being split into grants and loans among European Union members.

The funds are destined to be invested in clean technologies and renewables, to improve the digitalization of public administration services, to improve the energy efficiency of buildings, or to reskill and upskill the workforce through education and training to support digital skills.

These are just some of the areas where the funds are directed, which shows how governments provide funds for infrastructure improvements and one of the indirect consequences of spending these funds is job creation – a positive for any economy.

The United States

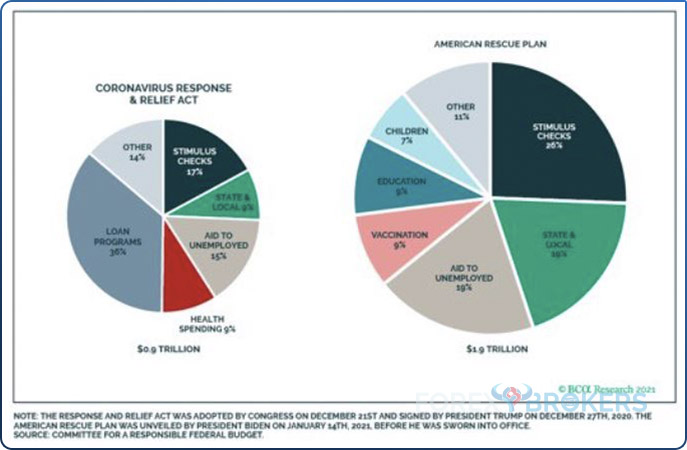

The most impressive fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic came from the United States. The Coronavirus Response & Relief Act added another $0.9 trillion on top of the American Rescue Plan of $1.9 trillion. A big part of this fiscal response came in the form of stimulus checks but also via programs supporting children, vaccination, unemployment aid, and loan programs.

America also has a plan to invest trillions of dollars to improve its infrastructure – yet another example of how easy fiscal policy can help an economy recover from recession. As a result of all these factors, the U.S. economy quickly recovered the lost ground.

Helicopter Money

Helicopter money is a concept first introduced by central bankers. Central banks around the world have a mandate to create inflation around a certain target – typically 2%. But they have not been successful in recent decades. For example, the Bank of Japan has had tremendous difficulties creating inflation, so the Japanese people lost trust in its ability to do so. At this point, it should be remembered that the consensus is that a certain level of inflation helps economic growth.

One of the solutions to create inflation was so-called helicopter money. This refers to governments sending people money for nothing, literally crediting their accounts with money to spend.

It was and still is a very controversial method, but the COVID-19 pandemic led to its implementation. While discussed in central banks’ circles, it was implemented as part of the fiscal stimulus in the United States, with households receiving direct checks from the government.

In Europe, helicopter money took the form of supporting people forced to stay at home under lockdown. Not everyone could work from home, and those that could not received direct aid from the state in the form of helicopter money.

But where did the money come from? As explained earlier, from borrowing. Even if interest rates were extremely low, governments found extreme interest in the international financial markets to fund their borrowing needs.

Check out our video about Monetary vs. fiscal policy:

Conclusion

Monetary and fiscal policies are responsible for the way financial markets move. Fiscal policy is as important as monetary policy, especially when traders are interpreting the state of an economy to trade its currency. However, the impact of monetary policy is more visible because the currency market reacts immediately to a central bank’s decision, even though the effects of that decision will not have an impact on the markets until much later.

Central banks have limited firepower when supporting an economy. When facing economic downturn, there are a certain number of things that central banks can do. When coupled with fiscal measures, monetary policy decisions have a stronger impact on economic recovery.

As always, the big question is, “How much is too much?” Now that investors and financial markets have seen how far monetary and fiscal policies can go, it may be that they will force the hand of policymakers in the future to react to any small recession.

The business cycle is made out of economic expansions and recessions, and it is normal for economic growth to slow down from time to time. Excessive borrowing and spending may lead to huge problems further down the road, such as loss of credibility or inflation rising beyond the central bank’s target.

To sum up, policymakers should find a balance between monetary and fiscal policy measures. The aim is to find the right way to stimulate economic growth while avoiding excessive borrowing or currency debasement.