Money is at the heart of economics, and the quantity of money in an economy often defines its shape and fate. However, the money supply or the money in an economy is different than the notion of money every one of us has.

Think of a regular household – it will always strive to make more money. Even by providing higher education to children, a household does so in the hope that they will end up living better, which usually translates to earning more. In this case, the money supply directly depends on the work done.

But in economics, the money supply has a different meaning. It refers to the total amount of money available in an economy.

The notion goes beyond cash in circulation. It also includes balances in bank accounts, for example.

One should not be surprised that the quantity of money differs from country to country. Therefore, this article covers different money measures across the world, with a focus on developed economies.

Even if some measures are the same, the aim is to spot subtle differences between different approaches to measuring money and how these differences ultimately affect the standard of living.

We will also touch on central banking and how central banks' actions regarding money supply work their way into an economy. Finally, we will look at the money supply effect on inflation through the lens of what happened in the past to understand what might happen in the future.

At the end of this article, the reader should be able to understand the role of money supply in advanced economies and how central banks' interest rate decisions affect the quantity of money available at any one point to businesses and households. Thus, their decisions on money supply directly affect exchange rates.

What Is Money?

Money is at the heart of our financial system. Before we had money as we know it, societies functioned through barter.

Barter means that there has to be a coincidence of needs between two parties exchanging goods. For example, one party may deliver apples, and the other one may pay for the apples with bread. Effectively, it means that apples were exchanged for bread.

If the goods sold are perishable, then the problem is that one may need to find a buyer for the products in due time. Hence, money goes beyond barter as it serves as a medium of exchange – the first important function of money.

To act as a medium of exchange, money must be difficult to counterfeit. Also, it must be readily acceptable by others and easily divisible.

Moreover, money must provide a store of wealth or value. Without fulfilling the function of a store of value, money has difficulty acting as a medium of exchange.

Finally, the last property of money is that it should be a measure of value and unit of account.

Fractional reserve banking is the pillar of money creation. Effectively, it means that only a fraction of a deposit to a commercial is held as a reserve, the rest is loaned into the system.

Central banks control the money supply in the economy by changing the reserve level or by engaging in other monetary policy decisions, such as changing the interest rates or buying and selling government bonds.

Countries have their own currencies, and, as in the Euro area, sometimes a group of countries shares the same currency. Effectively, it means that the euro fulfills all the functions of money for everyone in that area and not only.

Some countries decided to keep foreign exchange reserves in currencies other than their own. Here is a breakdown of the most popular currencies in terms of foreign exchange reserves.

Unsurprisingly, most foreign exchange reserves are held in the currencies belonging to the strongest economies – the US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, British pound, etc.

What Is Money Supply?

The money supply is the total amount of money in an economy. It refers to everything – coins, balances in bank accounts – everything. A key challenge for monetary authorities is finding the right balance between money supply and demand.

To do so, it is important to understand the relationship between the price level and money supply. Economists are aware of the quantity theory of money, which says that the money supply is typically proportional to spending.

By controlling the money supply, monetary authorities adapt their policies (i.e., interest rates) to the economic reality. Because all central banks' mandates in advanced economies include a price stability target (typically around 2%), their actions target changes in the money supply in such a way as to guide inflation back to the target level.

Let us use an example. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy has shut down. Few industries were kept alive, such as food and other basic necessities.

However, households and businesses still needed money for day-to-day expenses, so governments and central banks provided a lifeline by creating various economic stimulus packages.

In some cases, such as in the United States, people have received checks or free money as support. All these actions increased the money supply (i.e., money available at one moment) to such an extent that it created inflation.

Fast forward a few years later, and inflation is ravaging advanced economies. In the UK, for instance, it reached double-digit territory and stubbornly stayed there despite the recent central bank's actions. Similar high inflation rates are seen in other economies.

The explanation is that the increase in money supply (i.e., too much money) exceeded the spending. Or, too much money chases too few goods and services. Hence, prices rise, and authorities must step in to reduce the money supply.

How Do Central Banks Influence the Money Supply?

Central banks have several tools available in times of economic crisis and recession (too many recently). First, they lower the interest rates.

Until the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis, lowering the rates into negative territory was inconceivable. But reality showed us that a few years later, some of the most influential central banks in the world, the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank, have lowered the interest rates below zero and kept them there for years.

The idea behind lowering the interest rates is that businesses and households are encouraged to consume to spend money. This way, the economy recovers.

Commercial banks are not interested in keeping their excess reserves at the central bank. Thus, they lend money to households and businesses, contributing to economic recovery.

The opposite is true when central banks raise interest rates. The idea is to make it attractive for commercial banks to park money with the central bank, thus reducing the quantity of money available in the economy.

Second, central banks developed a series of unconventional monetary policies in the last decade. Quantitative easing started in the United States and was quickly adopted elsewhere.

Under such a program, central banks buy government debt and issue new money in exchange – money that the government spends, thus increasing the money supply. The reverse process, called quantitative tightening, has the opposite effect on the money supply. So far into the post-pandemic world, the decrease in the size of the balance sheet as a result of quantitative tightening should have been notable.

Only it is not, meaning that central banks are reluctant to remove the stimulus or do not have faith in the economic strength and still believe such appropriate balance sheet levels are needed.

How about the Demand for Money?

Demand for money excludes bonds and equities. This is the amount that households and businesses hold in the form of money.

They do so for three motives: speculative, precautionary, and transaction-related. Let's start with the last one.

This is money held for transactions and the amount is directly proportional to the changes in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Therefore, when the GDP increases, the demand for transaction-related money increases too.

Precautionary balances are savings. Both households and businesses have a buffer for unforeseen events, and savings also rise when the GDP rises and falls when the GDP declines.

Finally, the speculative demand for money is related to the return on other assets. It tends to decline when the return on other assets increases and increases when the prices fall.

Money Measures in the World

The second part of this article refers to money measures in the world. As you are about to find out, they are similar but adapted to each economy's particularities. Because of that, we will first discuss some economic and monetary background for each country before going into more detail about the money measures.

Each central bank uses its own way of calculating the money in the economy. Nevertheless, the measures are similar to help in terms of comparing different economies. In such cases, special measures were introduced, such as in the United Kingdom, when the Bank of England introduced one measure, called M3H, to be comparable with the measures produced in the European Union.

Money Measures in the United States

The United States economy is the biggest in the world. It is also home to the world's reserve currency, the US dollar.

Because of that, the central bank, the Federal Reserve of the United States, is the most influential central bank in the world. Other central banks follow its actions in the world as the global economies are often related. If a recession starts in the United States, it will negatively impact other parts of the world.

Five countries are responsible for half of the world's GDP – the United States, China, Japan, Germany, and India. The United States alone has an annual GDP of $25 trillion, and the currency, the US dollar, is in high demand.

US bonds are also in high demand. Moreover, the majority of international loans are in dollars, thus making the role of the dollar a crucial one for the financial system's stability.

As such, the monetary policies in the United States also impact other parts of the world. For instance, when the Federal Reserve is in a tightening cycle, it becomes more expensive for those countries that borrowed in dollars to repay their loans. Consequently, an accommodative Fed will act as an economic stimulus for emerging markets.

The Federal Reserve of the United States only produces two measures of money – M1 and M2.

M1

M1 consists of notes and coins in circulation and deposits on which cheques can be written. Moreover, demand deposits at commercial banks and travelers' cheques are also part of M1.

M2

M2 comprises M1 plus savings and money market deposits, time accounts deposits less than $100k, and various balances in retail and mutual funds.

M2 is the broadest measure of money in the United States and is often offered as an example of how the increase in the money supply is directly correlated to the rise of prices of goods and services (i.e., inflation) and the depreciation of the US dollar.

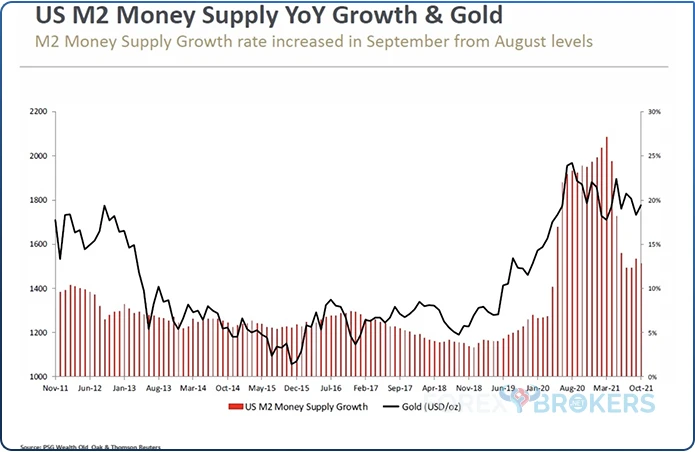

M2 Money Supply and the Price of Gold

Gold has historically been viewed as a hedge against inflation. As a result, when households and businesses expect the prices of goods and services to increase, they seek refuge in safe-haven assets, such as gold.

Therefore, if the M2 money supply shows the amount of money in the economy, and that amount is growing, the people expect that inflation will surge. As such, they will seek protection against it by investing in assets known as acting as a hedge. Of course, gold is not the only asset, as real estate serves as a hedge, too.

The chart below shows the direct correlation between gold prices and the M2 money supply. As the money supply expanded, investors bought more gold.

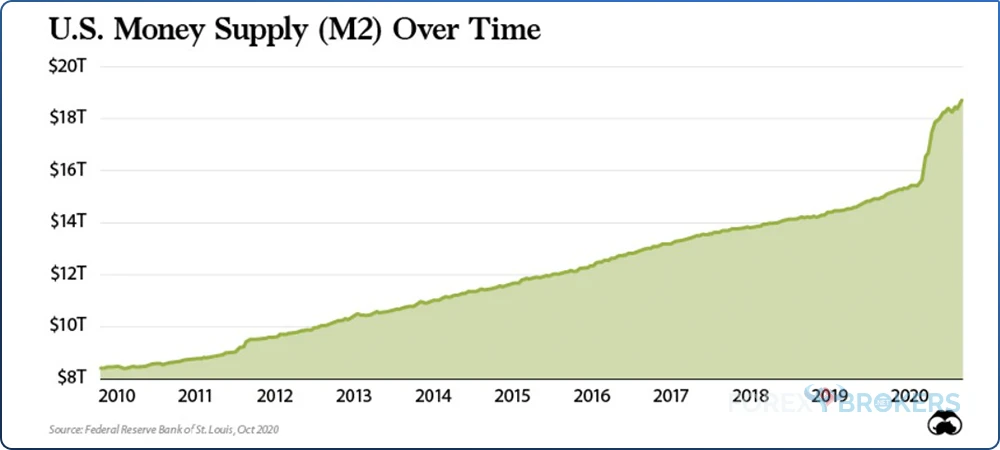

US M2 over Time

The money supply (M2) in the United States has constantly increased in the last decade. Since 2010, it has more than doubled.

In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, the Federal Reserve embarked on a new experiment, never done before – quantitative easing. By printing money, the M2 increased as the quantitative easing period lasted several years.

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Fed announced that it would embark on a process of reducing its balance sheet. Effectively, the opposite of quantitative easing is called quantitative tightening.

But only after a few months, the Fed had to abandon its plans. The pandemic has hit and it was time for new monetary and fiscal stimulus measures.

A close look at the chart above reveals how drastically M2 increased during the pandemic. In a very short time, trillions and trillions of dollars have been added to the financial system. And it is not only about the United States because the US dollar is the world's reserve currency.

What happens in the United States is "exported" to other parts of the world. So, for instance, if there is inflation in the United States, it is very likely that the phenomenon will spread to other countries with which the United States has trade agreements. Because the US economy is the largest in the world and has trade agreements with literally the whole world, it is easy to understand why the M2 money supply in the US is also important for the rest of the world.

M2 Starts Shrinking Again

The years of economic and financial crises and the COVID-19 pandemic have led to inflation finally picking up. But when it did, it surged, taking everyone by surprise, including the central banks.

To tackle the highest inflation levels in over four decades, the Fed began to raise the funds rate. It did so in what turned out to be one of the steepest tightening cycles.

By doing so, the Fed hoped to bring inflation down. But the interest rate hikes or cuts need time to make their way into the economy. Therefore, a lag exists.

Nevertheless, the effects start to show up. When writing this article, inflation has already come down from its highs.

Guess what happened with the M2 money supply? It has fallen by -2.4%, the largest decline on record (M2 data goes back to 1959).

Money Measures in the Euro Area

The euro is the common currency of twenty European sovereign nations. Until recently, only nineteen countries shared the euro, but since January 2023, Croatia has also joined.

Few have given many chances to the European project to survive. In particular, the common currency project was seen as flawed.

The reason, critics argue, comes from the central bank's inability to push tailored policies for each country. Instead, it must set the monetary policy for all of the countries forming the euro area.

But this has not been inconvenient for the European Central Bank (ECB). In the words of its former President, Mario Draghi, the ECB will do "whatever it takes" to protect the euro. It did and will do so in the future.

The European project brought together economies worth trillions of euros. For example, the European Union is a EUR 15 trillion economy.

Even though not all of the members of the European Union are also part of the euro area, many are. For instance, Germany, France, Italy and Spain are worth over EUR 9 trillion combined. In other words, much of the economic strength lies within the countries part of the euro project.

As mentioned earlier, the ECB is responsible for setting the monetary policy. Its task is daunting because each economy has its own needs. Also, inflation differs from one economy to another, so setting the same policy for all might not be the best way to reach a viable policy.

But like all central banks, the ECB did so by influencing the money supply in the economy. Here is how the ECB measures the quantity of money in the euro area: it looks at M1, M2, and M3 money.

M1

M1 is made of overnight deposits and notes and coins in circulation. It is the narrowest form of money in the euro area.

M2

M2 is a broader form of money. Besides M1, it includes deposits with a maturity of up to two years and deposits redeemable with notice of up to three months.

M3

M3 is the broadest definition of money in the euro area. On top of M2, it includes money market fund units, repurchase agreements, and debt securities with up to two years of maturity.

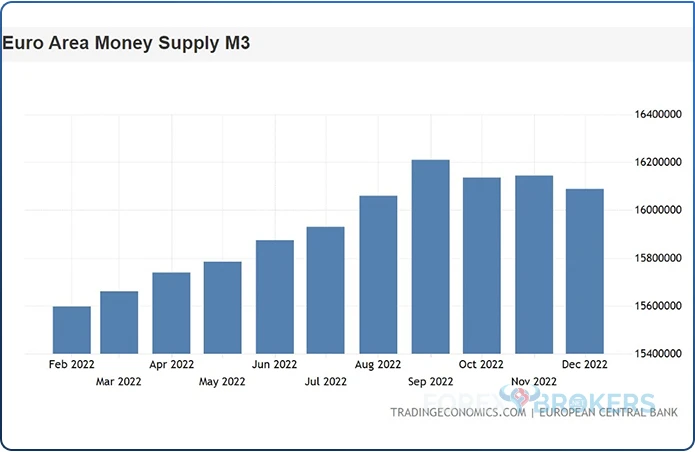

Below, the reader can see the M3 money supply's evolution in 2022, from February to December. It steadily increased until August and then decreased somehow.

Despite raising the three key interest rates from historically low levels, the ECB did not start the process of reducing its balance sheet size. At first, central banks introduced quantitative tightening as a cyclical tool designed to provide additional stimulus when needed and later, through asset sales, the stimulus should have been withdrawn.

Only that the second part did not happen, so far, quantitative tightening has been a one-way street, as it is yet to see if central banks will end up selling the assets.

Money Measures in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has always had a special role in Europe. It decided to leave the European Union in 2020 after a referendum four years earlier, but even when it was a member, it enjoyed a special regime.

The United Kingdom did not give up its currency. Instead, the Bank of England was and still is responsible for setting the monetary policy. When it left the European Union in 2020, the United Kingdom's economy represented about 16% of the European Union's economy.

Like most of the advanced economies, the UK economy is based on services. The services industry accounts for about 80% of the UK's economic output. Here, we can include the financial sector, the public sector, business administration, leisure, cultural activities, and so on.

But the UK economy suffered a massive blow in 2016. The people voted to leave the European Union, in a stunning outcome for core European supporters.

It took years to reach a final Brexit deal, in what turned out to be years lost for economic growth. In any case, the world moved on, and now the United Kingdom had to adjust its economy to the new realities. However, studies have shown that the GDP would have had a bigger growth rate following the Brexit vote if the UK had voted differently.

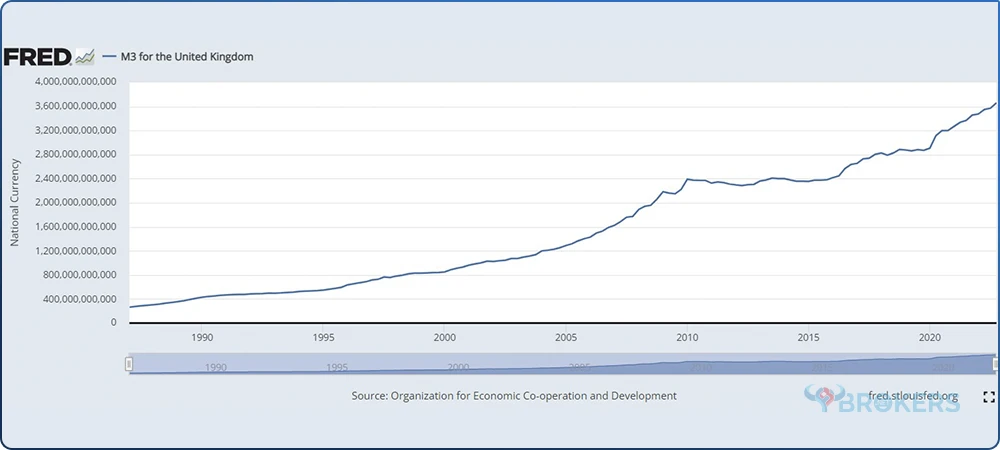

Like other things in the UK, the money measures are slightly different when compared to the ones in other countries. The Bank of England produces four measures of the money supply: M0, M2, M4, and one special measure called M3H.

M0

The narrowest form of money in the UK is M0. It comprises notes and coins held outside the Bank of England and Bankers' deposits at the Bank of England.

M2

M2 is made out of M0, and on top of that, it also considers all retail deposits. M2 is, in other words, an extension of M1 and by the end of 2022, it increased more than GBP100 billion versus the previous year.

The chart below shows that the M2 money supply in the United Kingdom has followed the same path as in the United States, with a major surge during the COVID-19 pandemic.

M4

M4 comprises M2 and three other components: certificates of deposit, building society deposits, and wholesale bank deposits.

M3H

M3H is a special measure introduced by the Bank of England with the aim of having a comparable money definition with the European Union. It comprises M4, and on top of that, it also considers foreign currency deposits in banks and building societies of both UK residents and corporations.

Money Measures in Japan

Japan is one of the largest economies in the world. Besides that, the Japanese economy is also one of the most interesting economies because of its unique features.

Demographics is one of those features. For example, while the Japanese people live longer on average than people in most parts of the world, the society suffers from a low birth rate.

This is a problem when planning for years ahead. A somewhat similar problem had to be dealt with in other advanced economies and the solution was immigration.

But in Japan, immigration does not work because of the unique culture. It is hard to integrate immigrants, and almost no efforts have been made to address this issue.

As such, the government and the central bank have to take special measures to ensure their goals. Most of the time, they differ from what the rest of the world does.

Bank of Japan – A Special Central Bank

The Bank of Japan deserves a special part in this article. This is because its actions differ from the actions of other central banks and thus, it creates volatility on the Japanese yen pairs.

The Japanese economy had suffered from a prolonged period of low inflation. Deflation was often registered (i.e., negative inflation rates).

When inflation turns negative, it creates a vicious economic cycle. Effectively, consumers postpone the purchase of products and services in the hope that their prices will decline some more in the future.

As a result, the economic growth disappeared, so the Bank of Japan stepped in to bring inflation to the 2% target. It used all the tricks in the book, learning from the Federal Reserve.

It has also embarked on quantitative easing. Only its program was so aggressive and applied to a smaller economy that it dwarfed what happened in other parts of the world.

The results appeared immediately, in the sense that the Japanese yen collapsed. For example, the USD/JPY exchange rate surged from below 80 to over 120. Such a steep depreciation is not healthy for economic growth, but it was a small price to pay for ending the deflationary period.

The biggest divergence came in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. As explained earlier in this article, faced with surging inflation, other central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, or the European Central Bank, have started to raise interest rates aggressively.

But the Bank of Japan did not.

Not only that it did not raise the interest rate, but it kept easing the monetary policy. As such, as the interest rates rose in the US and the Bank of Japan eased, the JPY tumbled again.

This time, the USD/JPY exchange rate surged from below 116 to over 150 when the Bank of Japan intervened twice. It sold dollars to buy yen but did not alter its monetary policy's course. Time will tell if its actions were right compared to what other central banks did.

The Bank of Japan calculates three measures of money: M1, M2, and M3.

M1

M1 is the narrowest measure, and it comprises just the cash in circulation.

M2

M2 includes M1 and certificates of deposit.

M3

M3 is the broadest measure of money in Japan. Besides M2, it includes deposits held at post offices and other savings and deposits held with financial institutions.

Conclusion

Money is one of the greatest things ever invented. It keeps the world accountable.

Managing money is challenging for a household, an individual investor, a company, or a nation.

Households must balance their incomes and expenses in such a way as to manage to pay the monthly bills and have something for the future. Companies manage money the same way as households but typically manage bigger budgets. Nations manage the money available in the economy at any point.

Therefore, by monitoring and influencing the amount of money in an economy, the monetary authority (i.e., a central bank) and the government control what households and businesses do or can do with their finances.

Measuring the amount of money available at any one time takes work. It differs across countries, but some similarities are noticed across countries and continents.

Societies are built on the concept of money. Without money, chaos would reign. Therefore, understanding money is critical not only for the trader or investor but also for households and corporations.

The money supply or demand in an economy tells much about the state of the economy and what is about to come. When the money supply increases, it is a sign of economic trouble, as the monetary authority increases the amount of money available to businesses and households to stimulate economic activity.

Money supply and demand are directly related to economic activity, the GDP. Sometimes, too much money chases a few goods, creating inflationary pressures. Other times, the opposite happens.

For the trader and investor, it is important to understand the concept of money measures, how it is created, and how governments and central banks use it to influence economic activity.